By Marga Torre

We all know that women and men tend to perform different jobs, and also that jobs typically performed by males come with more power and status. Indeed, sex segregation at work is the most relevant factor explaining the sex gap in wages, promotion, and authority. Therefore, accessing male-dominated fields is crucial for women’s economic and social advancement.

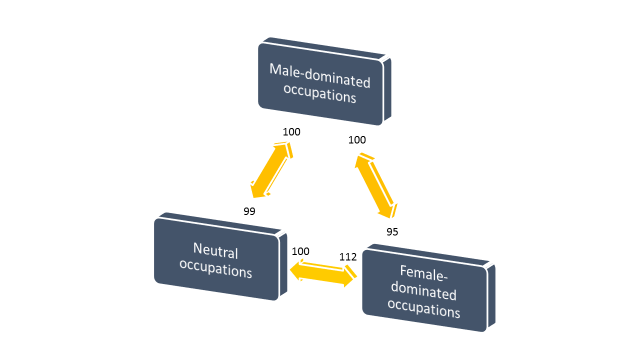

According to data provided by the National Bureau of Statistics, in 1970 about 70 percent of women in the US would have had to change jobs in order to be occupationally distributed in the same manner as men. By 1990, this percentage had decreased to 52, but it has remained rather stable since then. How is this possible when more and more women seem to be entering occupations traditionally dominated by men? The figure below explains why. As observed, for every 100 women moving from female- to male-dominated settings, 95 women do the opposite, thereby essentially maintaining existing levels of segregation. In other words, women’s increasing ability to “unlock the door” to male occupations has been accompanied by a substantial movement of women out of male-dominated occupations, reproducing the levels of segregation. In 1989 Jerry A. Jacobs labelled this phenomenon the revolving door, and it continues to be significant today.

Women’s occupational movement

Source: Calculated by the author using NLSY79 (1979-2010).

Why, then, do women leave male-dominated occupations—with their higher salaries and status levels—after clearing the barriers to entry? Understanding the flows between male- and female-dominated occupations requires us to examine women’s careers trajectories. Let us imagine two almost identical women starting to work in the same male-dominated occupation. They went to college together and have the same number of years of work experience. The only difference between the two women is that one started her career in the male sector right after college, while the other did so only after a period of employment in female-dominated jobs. Are they both equally likely to succeed in the male-dominated occupation? Despite their similarities, there are reasons to think that there is a higher risk of attrition with the second woman. This, I argue here, is because the notion of women’s work is imbued with assumptions and beliefs about the worth of the worker, which hinders their integration in the male sector. I use the term scar effect to describe the penalties associated with time spent in female-dominated occupations for women’s opportunities in male-dominated occupations.

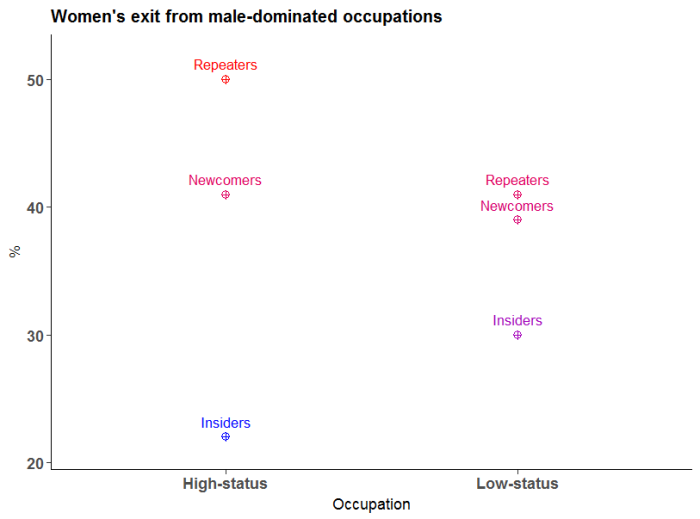

The figure below uses data compiled between 1979 and 2010 to show the exit probability for women switching from a male- to a female-dominated occupation one year after being hired. We distinguish three type of women with three different career trajectories: women already working in the male field (insiders), women recently arriving from a female-dominated occupation (newcomers), and women who have experienced previous episodes of attrition from male-dominated occupations (repeaters). Blue indicates lower exit rates, while the spectrum closer to red indicates higher exit rates—all after controlling for relevant demographic characteristics (age, level of education, parental and marital status), and work-related features (tenure, hours worked, year of experience).

Source: Calculated by the author using NLSY79 (1979-2010)

As observed, the probability of moving to a female-dominated occupation one year after entry is significantly lower for women who have been working in the male field than for women who have recently arrived from female settings. More specifically, the probability of attrition to female occupations is 22 percent for insiders but over 40 percent for newcomers in the case of “high-status” professionals. The probability of exit for repeaters is higher still at about 50 percent, almost twice the probability of attrition for insiders. It could be that co-workers perceive previous episodes of attrition from male-dominated occupations as an indication of failure, or of women’s inability to fulfill their responsibilities; such sentiments and lack of confidence in their abilities could raise the probability of such repeaters exiting and returning to a more supportive environment. The differences among women in low-status occupations are less pronounced. Attrition rates range from 30 percent for insiders to about 42 percent for repeaters, with newcomers at around 40 percent. In short, attrition is substantially higher for newcomers than for insiders among both categories of workers, while professionals suffer extra penalties for earlier episodes of attrition.

This evidence points to the scar effect of female work; in other words, women’s attrition can be partly explained by newcomers’ disadvantages with respect to both men and women employed in male-dominated occupations. This effect is more pronounced in the most prestigious occupations. Incumbents in male-dominated occupations tend to penalize women arriving from outside the world of men’s work, whose presence is seen as inappropriate or peculiar, more than women whose career paths have followed men’s all along.

———————————————————————————————

Marga Torre is Assistant Professor in Sociology at University Carlos III of Madrid (Spain). Her research interests include gender, occupational segregation, labor markets, and social media. Her work has recently appeared in Social Forces, Sociological Perspectives, and International Migration.